Puck: What a cat taught me about dying

Loving him was like loving a river

More than anything, I remember how he died. That is not to say his life wasn’t special. It was, in the wild way a once-feral cat’s life tends to be. But he wasn’t the sort that people go on about, not while he lived, and not after he was gone. He didn’t make that kind of impression, never quite tame, never quite known.

Loving him was like loving a river: dependable, wise, enigmatic. To understand how he left, you have to know how he lived. This is that story.

We were liveaboard sailors docked in the small annex of a large marina at the east end of Long Island, New York. Every day, returning from work, the fisherman, who lived in the one slightly shabby structure at the end of an otherwise upscale row of waterfront homes, gave the trimmings of his catch to the resident colony of feral cats. Though he fed them all, we’d heard and believed that he drowned any kittens he caught.

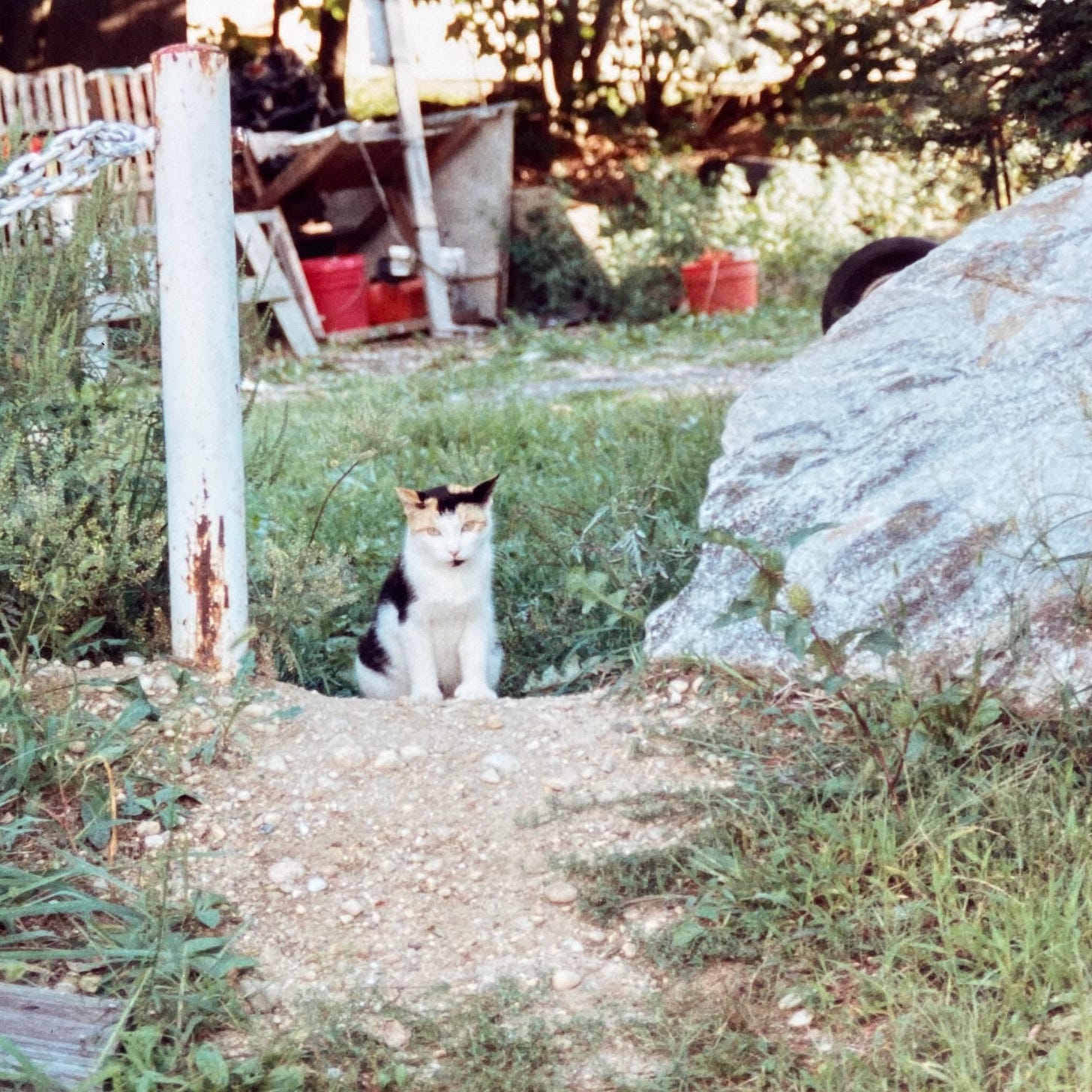

At this time, there were ten or twelve adults, a coursing mix of blacks and grays, whites and oranges, on the fringes of human interaction. At night we heard them yowling out their hierarchies and affections.

When we noticed how frequently the calico visited the abandoned boat a few slips away from ours, disappearing beneath its faded green cover, I assumed she was tending a litter and sent my husband to investigate. He returned perplexed. Yes, there were babies, he confirmed, but he couldn’t get near them because of a mean one blocking the way.

“Mean?” I quizzed.

“Vicious. It was hissing and spitting,” he said, half amused, making small clawing motions with two fingers.

“They’re babies. How mean can they be?” I laughed.

Climbing aboard, I ducked below deck to discover three scrawny kittens, two wedged silently into a break between the cushions and one standing straddle-legged above them, projecting as much ferocity as his 5-by-5-inch frame could manage.

We named him Puck, after the woodland sprite in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. His sister became Cobweb, another fairy and a part I’d once played in a summer Shakespeare festival. We found a home for the third one and began our life as first-time feline owners.

Having cats made sense—more than dogs, anyway—and these two took to our boat with ease. We had visions, then, of living aboard indefinitely, of cruising to warmer places in winter and cooler places in summer, of making our way as we could. Instead, before our next birthdays, life took us in another direction, to human babies and a farm neither north or south, where two half-wild cats and their people could roam without restriction.

Within a year, Cobweb mysteriously lost her voice. The first vet wanted to send blood work off for an expensive battery of tests. The second cut to the chase; she knew and confirmed what was wrong. Both cats were diagnosed with Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV), a disease not unlike the human version that was likely to result in secondary infections that could take their lives in as few as five years.

We were told it wasn’t uncommon in feral cat colonies and that it had likely been transmitted by their mother. She couldn’t have been much more than a year old herself when she had her first litter—those three kittens we took from her when they were so young. Her life was difficult even without an incurable disease. I wondered if she was still alive.

Anticipating frequent illnesses and trips to the vet, I dreaded the years to come. Whether it was the professionals in their lab coats, the other animals, the smells, or the sounds, Puck despised those offices. After noting his dirty ears, one vet recommended we take up the habit of cleaning them. Moments later, as she and her technician tried to administer a shot, the patient broke away from their grip in an explosion of writhing muscles. They doubled down, but he did it again.

“Actually,” the vet said, “I wouldn’t worry about his ears.”

“Actually, I wasn’t planning to,” I replied.

Our cats’ lives went on to be unexpectedly normal for a very long time. Despite the presence of a lurking killer, their emergencies were not so different from those experienced by healthy cats. Cobweb, never much for adventure, stayed close while Puck went prowling. To our horror, he captured and dragged home creatures from land and sky—rodents, reptiles, bats, birds and bunnies. He deflected raccoons and screamed at foxes. He swatted our children when they poked him once too often and pressed his teeth into our arms when he was tired of being touched, though he seldom broke the skin. When, four days after we noticed the squinting, we finally took him in and a vet removed a half-inch splinter from just below his eyeball, I marveled at his stoicism.

We still talk about the day Jim decided Puck needed a bath. Disregarding my warnings, he carried him away, shutting the bathroom door behind him. What happened next is between the man and the cat. Suffice to say there was a horrible shrieking, some notable thumping, and the flash of a feline flying out the window.

In the spring of his twelfth year, Puck went into decline. Some days, the only way I could coax him to eat was to offer soft morsels by hand. I remember talking to him gently, explaining why he needed food and how grateful I was to feel his rough tongue on my open palm.

As his sturdy, 14-pound body shrank away, his strength went with it. He no longer climbed the stairs to our bedroom and rarely left the house, choosing instead the comfort of soft places on the farm cottage floor.

To end his suffering and spare him the terror of another trip to the vet, we arranged for the good doctor to come to us. But at the appointed time, Puck disappeared. Thinking he couldn’t have gone far in his frailty, I searched the house and property in ever-widening circles to no avail. Moments after the vet’s car left the driveway, Puck walked back into the kitchen. I’ve never received a clearer message from an animal.

“My terms,” he told me. “I’ll do this on my terms.”

With her steady, unassuming manner, his sister slowed, too, but we never imagined she would be the first to go. She seemed tired, older, not ill. Her symptoms came on suddenly one morning, and by afternoon we all gathered in our skilled veterinarian’s office to support Cobweb in her final moments.

Home and heartbroken, I made my way up to bed to sob where the kids would be less likely to see me. When I pulled my face from my hands, there stood Puck. It had been months since he’d climbed the steep stairs to our loft.

Three weeks later, just as he had when he dodged the vet’s house call, our sweet fellow made his wishes clear once more. His wandering days were long over. He moved as little as possible to conserve what energy he had left. That day—a Monday, May 23—he was determined to get outside. Ignoring his pacing at the door, afraid of what he might encounter, afraid to let him go, I didn’t want to listen.

His will prevailed, as it had so many times before. I carried him down the porch steps, set him gently in the grass, and walked away to give him space to leave. We found him later that evening under the house.

Twenty years and so many losses later—and so many joys, too—I still think of Puck as the one who first taught me what it means to face dying, to see it as part of living, not something I can control but that I can meet with courage if I learn the language for it.

Dying comes. I owe it to myself and those I love to speak of it, to soften into it rather than turning away. When I do, I become more present to the days I have and the people I’ve been given to experience them with.

Like flowing water, Puck was never fully ours. But standing at the edge of his departure, I learned what it means to bear witness, to release what I cannot hold, and to honor the mystery of what comes next.

~Elizabeth

When it comes to understanding our world, animals can be amazing teachers. But you also teach me. The best part about being a writer here is getting to connect with readers in the comments! I hope that opportunity feels special to you, too, and that you’ll share some reflections today. Has your pet’s voice ever been particularly apparent? Are you learning how to face what frightens you? Who, or what, was your Puck?

Want to read a little deeper into our sailing experiences? Coincidentally, Staying Afloat was written almost exactly one year before this essay and describes our earliest adventures on the classic wooden yawl, Tempo.

Please also consider lifting up this and other’s writing efforts by clicking the like button (💚), restacking (♻️), or both. There is no better way to support what we do. That small gesture makes a world of difference to us!

Finally, If my words and this community bring value to you, I hope you’ll think about joining in for either a paid subscription, which can be accessed here, or a one-time tip, available here. For those who have the means, it means the world to me! I want to continue creating avenues for connection that aren’t tied to our wallets. For that reason, I continue to keep access to these posts open to everyone.

I’m grateful for all the ways we show up together here. Thank you! Until next time, take good care.

This is such a tender and loving story that helps us with the nearing death of our very old cat, and the inescapable death of my fairly old person. The unknowable mystery of death is something I probably won't come to some sort of understanding about until it is facing me directly. Until then, this story you have told, and others like them are comforting.

Beautiful, Elizabeth. Weren't you all the lucky ones--Puck included. 💕