Sharp shards

Noticing harm and what it teaches me about honoring life

If you prefer to listen, you’ll find an audio version, read by me, here. ⬇️

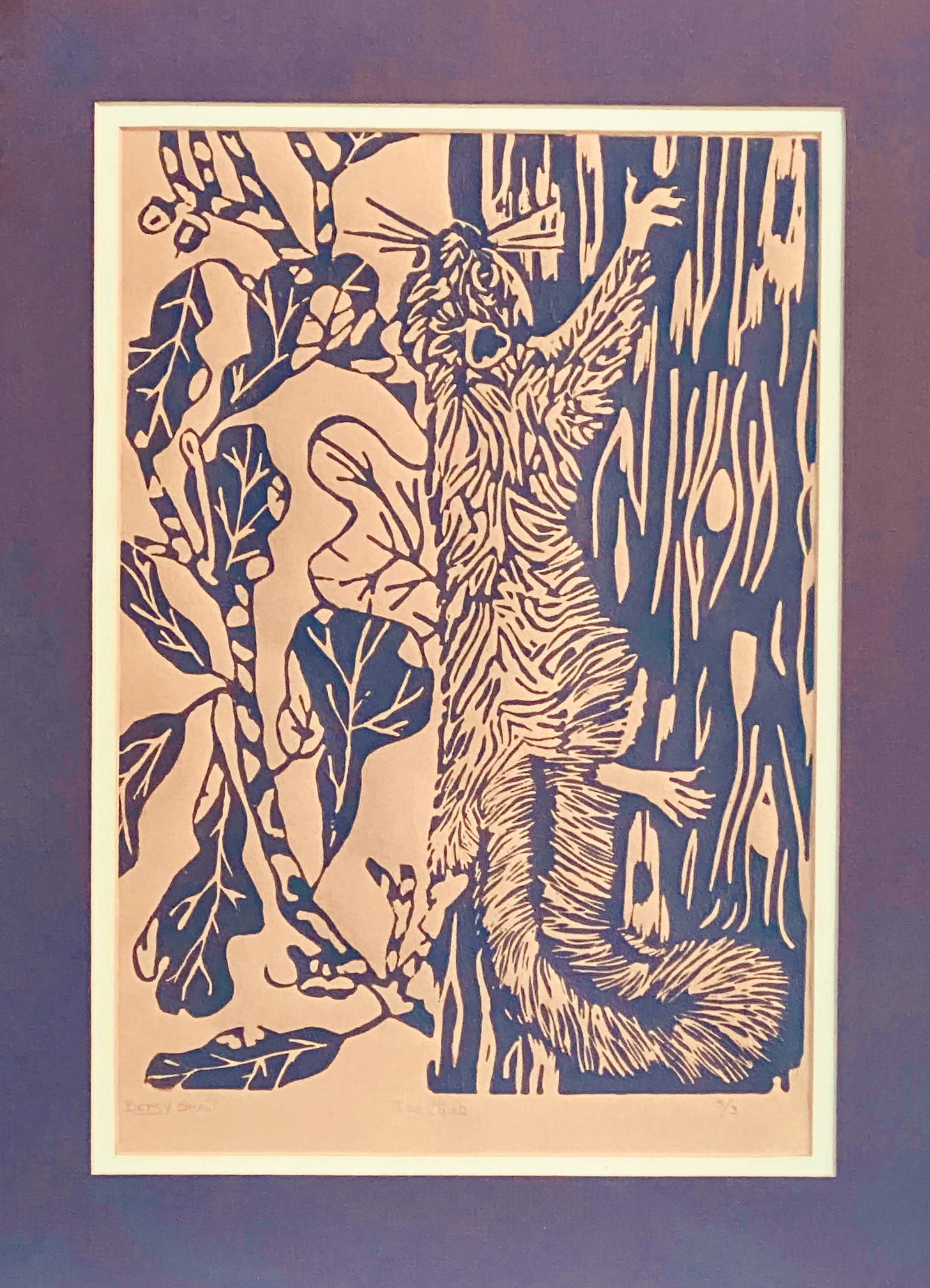

“I’m going to have to deal with some of these guys soon,” my husband says after a cadre of squirrels makes quick work of the chicken wire I’ve secured over my potted kale plants. I grow hardy greens in these pots every winter, but this year the fuzz-tailed Houdinis are decimating them before my eyes. It feels like a losing proposition.

I live in a small, rural town where critters with abundant food supplies flourish in the absence of natural predators. The more prolific they become, the more damage they do, ravaging gardens, stripping bark from young trees, chewing table legs. My husband is inclined to control them precisely, reducing the population until we reach a better balance.

The first few times he mentions it, I mutter and make disagreeable faces. Eventually, he’s winning me over. “Only if we can find someone who’ll take them for food,” I say, because I hate the idea of killing something just to kill it. I spend a few minutes browsing recipes for traditional Brunswick stew but can’t quite justify learning how to clean squirrels given how little there is to work with.

Later, prefacing her comment with sufficient sensitivity, one of my kids notes that they’ll be food for something whether we eat them or not.

I am thirteen, and my family has just moved into a new house on a wooded lot in suburban North Carolina. My mother, only forty-seven, has lost both of her parents just three weeks apart. She uses the inheritance to build what she thinks will be her forever home. Creating something lasting from that kind of loss serves as a stand-in for the therapy she never seeks.

The house itself seems to understand this, not dominating the land so much as settling into it. One tree in particular, a substantial hickory, stands exactly where the deck is meant to go. Instead of cutting it down, they build around it.

I can still conjure the sound of the squirrel dropping onto the deck with a sickening thud.

To my young self, this feels logical—obviously the tree should be saved. Only later do I realize how rarely people opt into that kind of accommodation. Every fall, in its wide, waving arms that arch above the deck, the hickory produces an abundance of nuts, and every fall, the squirrels cut them into sharp shards that wedge between boards. My parents spend untold hours on their hands and knees, using table knives to pry them out one by one. It is tedious, physical, deeply unglamorous work that is never quite finished.

At some point, my father decides there is a better solution.

He frames his assault on the resident rodents as a necessity and takes up a post inside the barely-open sliding door, a few feet away from that stately tree. My tender heart and I wander into the kitchen just as he fires a shot, and I can still conjure the sound of a squirrel dropping onto the deck with a sickening thud. My protests annoy my father who tells me to take myself to another part of the house.

Dad is an avid waterfowl hunter and sometimes travels west to hunt larger game. Guns are familiar to me, insofar as I am accustomed to their polished, upright presence in the glass-front cabinet in the basement. I think nothing of eating what my mother prepares from the spoils of his outings: tiny quail smothered in mushroom gravy, hearty roasted duck or goose glazed with sweet fruit, moose burgers, elk steaks.

What’s unfamiliar is witnessing the moment when an animal goes from living to dead. There is no discussion, no acknowledgment that something irreversible has happened. The squirrel is a problem; the problem is addressed, and my unease is treated as an inconvenience, leaving a persistent impression that I won’t understand for a very long time.

My husband and I consider ourselves fortunate to raise our children on a farm. We live there for thirteen years, long enough for the rhythms of tending and loss to become intuitive. He is busy running a furniture-making business, so the garden and the flock of laying hens are mostly mine to manage. Death is everywhere—chickens sick beyond saving, chickens beheaded or carried off by predators, reptiles, insects, garden plants, weeds, and every kind of creature our part-feral cat takes pleasure in offing. When you are that close to it, life is always brushing up against its end, and stewardship requires constant acknowledgment of what is fragile and finite.

I never love any part of it. I don’t even like it, but I do it with honor for the life being given and the sustenance it allows.

When the hens grow too old to lay productively, we cull them ourselves, with a small group of helpers. Once a year, fifty birds in a single day are then sold as stewing hens to our devoted market customers. It is nothing compared to what many farmers do, but it feels like plenty to me. I don’t sleep for days beforehand as I rehearse the reasoning over and over again: this is part of eating; this is part of care; everything we consume involves the death of something.

I tell myself that if I am going to eat meat, I must be willing to kill it, and that there is something dishonest about outsourcing the violence while enjoying the benefits. I think I’ll learn how to do it quickly, cleanly, with as little suffering as possible, but I only use the knife on a chicken’s throat once. It takes me two tries, and I feel horrible for the bird. From then on, I maintain other positions on the processing line, leaving the sticking, as we call it, to those more confident.

I never love any part of it. I don’t even like it, but I do it with honor for the life being given and the sustenance it allows. After several seasons of second guessing my hesitations and wondering why this continues to weigh on me, I realize that complete acceptance would dull the gravity of the sacrifice. I don’t want that. I want the act to stay difficult, weighty, acknowledged.

Though I can’t identify it the day he decides to take charge of the squirrels, what I feel in the gruff exchange with my father is a tension between his need to solve problems and my own need to appreciate life. His irritation with me is human, shaped by the expectations of his generation and gender—the demand to act decisively, without visible emotion—but it unsettles me with how it pushes past the caregiving I so desperately want to preserve. It’s not malice, only a difference in how we approach what we owe to living beings, a distinction in moral awareness that has been alive in me for as long as I can remember.

In our backyards, squirrels can be treated as problems to be managed—aggravating, low-stakes.

Beyond the property line, that same lack of regard can be catastrophic.

Renee Nicole Good, a mother of three, a wife, a friend and neighbor, someone with a whole life, loved ones, and dreams, is shot at close range, in broad daylight, by a man authorized to carry a gun in the name of the state. She is neither verbally aggressive nor armed. I read account after account of how she is killed. I don’t watch the videos, because I already understand the magnitude of a life ended, and I want to keep my attention on what it takes to bear that responsibility.

I do not know if respect—for life, for the inherent worth of a human being—can ever be fully restored once it has been discarded

Around the world, and with horrifying frequency in this country, lives are taken with guns backed by authority, and the deaths are folded into policy debates before grief has even begun. Renee’s is one such life among many. I do not know if respect—for life, for the inherent worth of a human being—can ever be fully restored once it has been discarded, once someone sees it as expendable.

What I do know is that the work of bearing witness to what unfolds when care is abandoned, of acting with integrity and attention, is ours to do, even when it is exhausting, even when what we are able to do feels impossibly small. I know that when we go looking for leaders the criteria for selection should extend far beyond political affiliations and what we want to believe. The capacity to lead should be measured by moral courage, by a willingness to not just acknowledge harm but also take responsibility for it rather than deflect or deny it.

So many of us are out of balance, teetering between paralysis and rage, undone by what’s been lost. We can’t do much, but we are doing what we can. Is it enough—to notice, to care, to tend what remains worthy, to honor the goodness that persists despite it all? In the face of so much destruction and suffering at the hands of those in power, I’m not sure. But I am certain that if we look for them, opportunities to act with respect, even reverence, are never hard to find. And, in the absence of the tectonic shifts we hope for, they become everything.

~Elizabeth

Life is full of times that catch us off guard—reminders of fragility, the sudden clarity of what it means to care. If this essay nudged you to notice anything in particular, I’d be honored to read about that in the comments.

For a companion reflection on care and persistence, you might also read Every Afternoon at Five O’Clock, among my most popular essays, where a daily call to my mother and the rescue of a baby squirrel became lessons in attentive tenderness.

If you found something here worth remembering, I hope you’ll pass it along to someone who might feel the same.

My essays are always free to read, and I consider it a privilege to share them with readers who bring thoughtfulness and heart to this space. To those who choose to support my work, thank you: your paid subscriptions are truly a gift, but your encouragement alone helps me keep writing with the care and attention these subjects deserve.

You know those amazing jumps that a squirrel can make from the tippy-tip of a branch of one tree to the tippy-tip branch of another? I love the leap you made from one part of your essay to the other. It's sobering. It's everywhere. Someone recently said "Humans have always been a mess; and we have always found the ballast to keep sailing." I think I just merged two quotes, but the idea is very Stoic: the world being a mess doesn't mean we change who we are and what we do to find good and promulgate joy.

I’m with you. This is not what I expect my country to be.