How Facebook paid me $35.30 (and why that's not the point)

Drink up, friends!

An audio reading, recorded by yours truly, is available here. ⬆️

Last week, I received a check from Facebook for the oddly specific amount of $35.30. It took me a minute to piece it together: this was my slice of the $725 million class-action settlement they paid out for treating our personal data less like a protected asset and more like the free peppermints you grab by the handful on your way out of a restaurant.

I don’t remember signing up for this payout. But sometime in 2023, probably with 14 browser tabs open and a faint sense that someone, somewhere, was getting away with something, I must have filled out the right form. And now here it was: the physical embodiment of justice, apparently worth the price of a couple of specialty cocktails.

Naturally, I typed “Facebook settlement” into Facebook itself. What a mistake.

Near the top of the results was a woman who was outraged—Outraged!—that Facebook had used her data without permission. To prove how upset she was, she posted a photo of her settlement check with her full name and home address clearly visible. The modern privacy paradox was tied up with a bow: I am furious at this invasion of privacy, and here is all my private information so you know I mean it.

I stared at her post, stuck somewhere between bemusement and bewilderment. People want their data protected; they also want witnesses to their indignation. Those two desires rarely shake hands. Her post reminded me of how often we’re put in contradictory positions around technology, asked to defend our privacy while encouraged to share so much of our lives publicly.

Still, the moment stirred up other mental sediment, sparked by time recently spent at the holiday kids’ table, now populated by people with rental agreements and car payments but whom I still remember losing baby teeth. Dessert was happening on top of stomachs already at capacity when the conversation wandered to ChatGPT. I asked, genuinely, who used it.

A 24-year-old said she sometimes did, for research paper outlines. At this, another young woman recoiled like the word itself carried a biohazard warning.

“Why would you do that?” she demanded. “It’s killing our planet!”

It was the perfect blend of moral alarm and inherited eco-guilt, something children of environmentally conscientious parents are especially gifted at. A debate followed about data centers, server farms, water usage. All valid concerns, but what struck me was the familiar shape of the conversation. Once again, I noticed, we’d been handed responsibility for a system we didn’t design and can’t meaningfully alter unless we personally plan to swan-dive into a cooling tower and short-circuit something.

It reminded me of jaywalking. Before cars dominated the streets, pedestrians were the default users. When traffic deaths rose, automakers and local governments promoted the term jaywalker and campaigned to shift blame onto pedestrians, effectively reframing the problem as individual irresponsibility rather than industrial expansion.

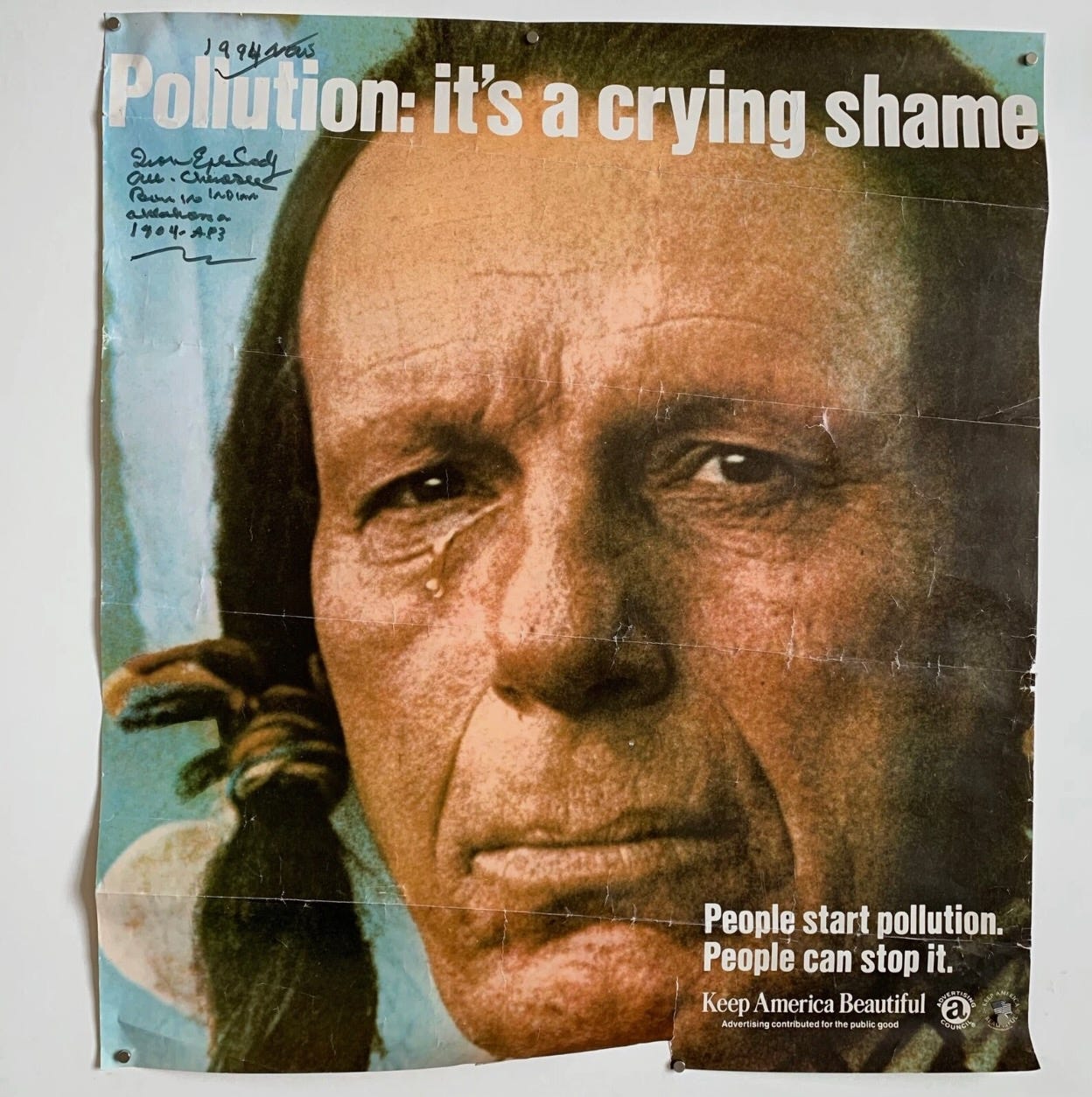

Then there were the 1970s Keep America Beautiful ads, featuring a solemn ‘Native American’ (actually Italian-American actor Iron Eyes Cody) shedding a tear over pollution. The campaign, funded by multiple corporations including Coca-Cola and Pepsi, framed littering as a personal moral failing rather than a systemic issue of manufacturing waste. The problem, it implied, was you, the littering monster. “People start pollution,” it scolded. “People can stop it.”

The pattern repeats ad nauseam.

The term carbon footprint was popularized in the early 2000s by BP, as part of its rebranding from British Petroleum to Beyond Petroleum. The implicit message: while industrial emissions drove climate change, individual actions, recycling or cutting back on single-use plastics, were positioned as the responsibilities of ordinary people.

More recently, financial literacy arrived as a polite way of implying that if poor people stopped buying coffee, rent would magically become affordable. The solution to global problems is always, somehow, that you should have tried harder.

In every case, mass-scale harm is recast as a question of individual failure.

There is a long tradition of massive systems breaking things while convincing us the shards in our hands are our fault. So when the AI environmental debate kicks up, it rings the same bell. We agonize over the carbon cost of a single AI query while the machine hums along with the subtlety of a runaway train.

Back at the kids’ table, the conversation ended in the usual détente. Everyone agreed something felt off; nobody agreed on where the “off” was located or who should fix it, or how.

Later that week, I tuned into a Big Think piece about large language models, how they learn, what they reflect, and what we assume they can do. It made me feel both better and worse, which is how you know you’ve encountered quality tech commentary.

The featured guest, Dan Shipper, pointed out that people once felt suspicious of books. Books! We eventually learned to love them, romanticize them, arrange them in our homes like colorful emotional support pets. The same thing happened with cars, computers, microwaves, cell phones. His point was that new technologies do not feel natural to us until we’ve lived with them long enough. Novelty invites fear; familiarity invites affection, or at least a sense of understanding.

And yet it is also sane to admit that AI is different in some ways. It’s bigger, faster, stranger, more powerful. Being unsettled by it doesn’t mean we’re ignorant. It means we are paying attention. Shipper’s point about fear evolving into familiarity made me realize that the anxiety in this instance isn’t about novelty as much as it is about scale and speed. These tools aren’t unsettling just because they’re new; they’re unsettling because they’re vast and remaking the world at a speed that outpaces understanding.

I keep circling the idea that the systems governing our lives are enormous now: the algorithms, the digital cookies that sweeten the deal for companies while rotting our sense of autonomy, the corporate greed, the rules we never got to vote on. And in response, we cling to tiny acts of agency: refusing plastic bags, avoiding plastic straws, taping over webcams, feeling guilty about chatbot prompts, applauding ourselves for unsubscribing from one more marketing email. These things are not meaningless, they’re just not the whole story. The work of change does not begin and end with personal purity tests. It requires better targets for our outrage than our own habits, and a willingness to participate in solutions that demand more than the minimum sacrifice.

For a day or two, my $35.30 sat on the counter, tucked under the edge of my laptop. I kept looking at it as if it might whisper a secret about the state of the world. But of course it didn’t. It was just my tiny portion of a massive machine saying, “Our bad. Here’s a little something to take your mind off the reality of it all.”

I’m not resigned, or naïve, or thrilled to be a cog in the great data-harvesting contraptions of the modern age. I also don’t have realistic solutions, which is uncomfortable. I suppose the best I can do right now is stay alert to what’s happening, keep my sense of humor intact, and resist the idea that my only job is to feel guilty about problems too big for any one person to fix. Awareness isn’t everything, but it’s not nothing either.

And if Facebook wants to buy me a drink in exchange for knowing I once liked somebody’s dog photo in 2015, well, fine. Cheers!

~Elizabeth

Now, the floor is yours! What’s the wildest “thank you for participating in my data collection” moment you’ve had? A check in the mail? A weird email? An ad that seemed way too personal? Share it—I want to know. Your comments and reflections are always a highlight, and I love seeing readers spark conversations with each other.

If this essay resonated, you might enjoy Meet my new pal, Shazbot where I describe my conversation with a fledgling AI chatbot and what it revealed. To further explore the theme of focusing on what we can and can’t change, check out Obsessing over someday

Everything I write here is free to read, and I’m deeply grateful for each of you who subscribe, share, comment (this button —> 💬), like (this button —> 💚), restack (this button —> ♻️), offer a one-time donation, and show up week after week with me here.

Your attention and curiosity are what make this space meaningful—every measure of support, paid or not, lands like a lifeline. So thank you, truly, for being here.

It's good to know what while my mind is batting around like a moth against a lightbulb, someone is out there writing a cogent piece that puts a shape around my feeling that "somethin' ain't right." Thank you, E. Your Chicken Scratch should get a Pullet Surprise for writing.

I appreciate this so much: "I suppose the best I can do right now is stay alert to what’s happening, keep my sense of humor intact, and resist the idea that my only job is to feel guilty about problems too big for any one person to fix." A good maxim for living in the midst of collapsing and emerging world orders.